As more and more teams are coming on board with Chef, I’ve begun to standardize our pipeline and ensure that everyone meets quality gates for the infrastructure they are creating. This started with finally figuring out how to get Test Kitchen working with Windows, then quickly migrated to getting it running in TeamCity. Our entire division uses TeamCity for configuration management, so it’s something that I needed to plan out carefully in order to make the Chef pipeline feel like it’s a part of a team’s normal build process.

Project Structure

With this in mind, we created a Chef subproject inside each team’s existing project. We want them to have ownership when Chef infrastructure breaks and to take action on problems, just as if the problem happened in their own software build.

We then created a Chef

Cookbook build template at the

<Root Project> level that all cookbooks can use for their own builds. This template defines a cookbook parameter that

enables the build steps below to know where the cookbook is in source.

Version Control Settings

We’re not really sure about how we approach testing at the moment when it comes to dependencies. If a cookbook is very young or if we are testing a lot of things at once, we might want to use relative path dependencies to other cookbooks. Or we might want to use data bags at some level. So we’ve decided on the build agent itself to mimic a Chef repo and then test it that way. We do this through a checkout rule, like this:

+:.=>cookbooks/contributorsThis means that the contributors cookbook will go to the cookbooks/contributors repo relative to build working directory.

Build Steps

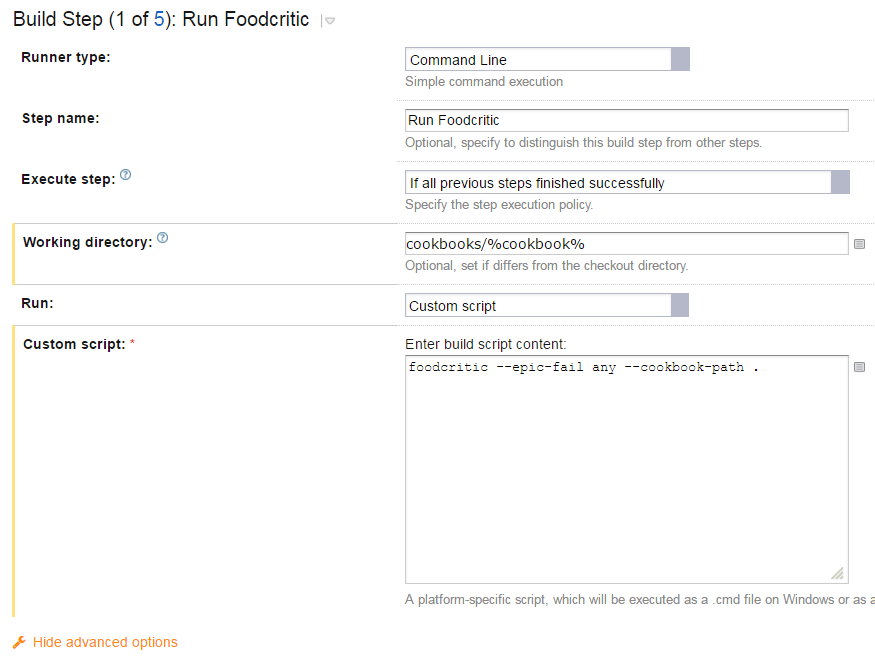

1. Run Foodcritic

We want to do Chef linting first before we get into further testing, so we run foodcritic. This is done simply by creating a Command Line runner with the foodcritic command:

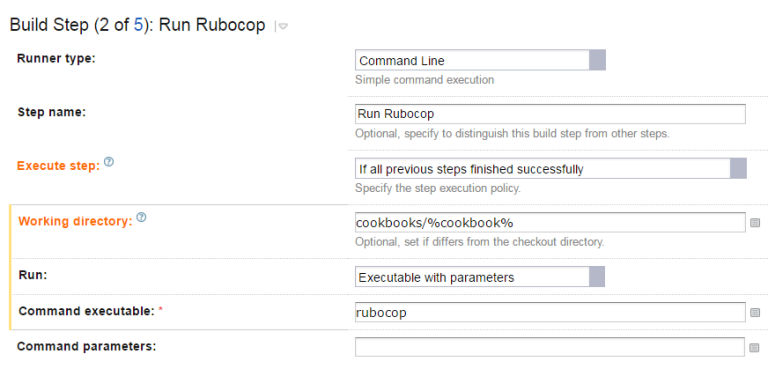

2. Run Rubocop

Once foodcritic runs, we want to finish our cookbook linting with rubocop:

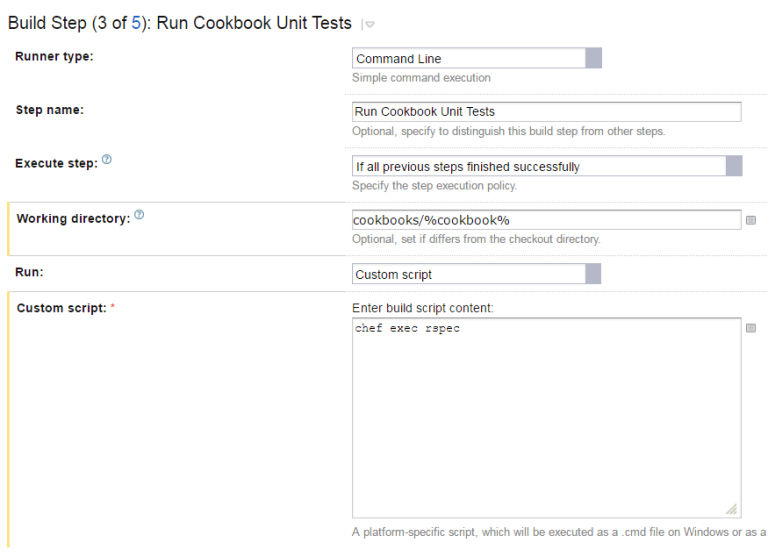

3. Run Cookbook Unit Tests

I’m not a huge fan of ChefSpec because I believe they mock too much out and end up not adding a lot of value. But I do think having at least one there that ensures that your code will converge is immensely helpful. It’s much better waiting the few seconds to ensure that code converges than the few minutes to wait for kitchen to tell you the same thing. So I put the step here:

Update: actually just before this published, I removed this. The Chef Spec unit tests required too much ruby expertise to be helpful. Plus people are working well with kitchen and learn to rely on it instead. So as of yesterday, this step was removed.

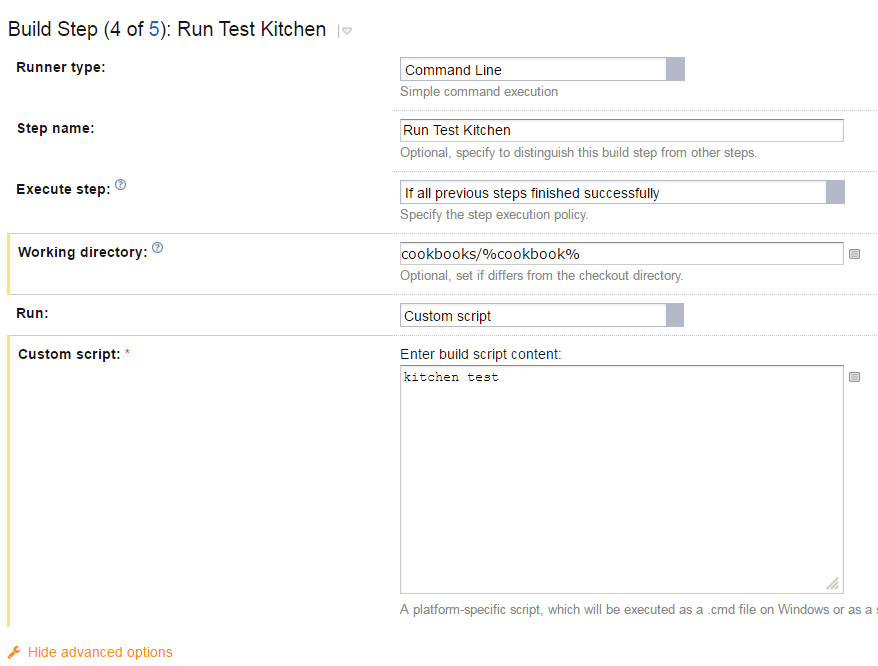

4. Run Test Kitchen

And now for the magic! I need to run Test Kitchen. If I’m using vagrant, I need to have a physical build agent to do this on. If I’m running azure, I need to have some credentials set up on the build agent. All of that configuration is handled through Chef itself, so at this point all I need to do is run the command itself:

Kitchen test will do a create, converge, and verify. It runs through the whole process. And I’ve tested that if it

fails, the build will fail.

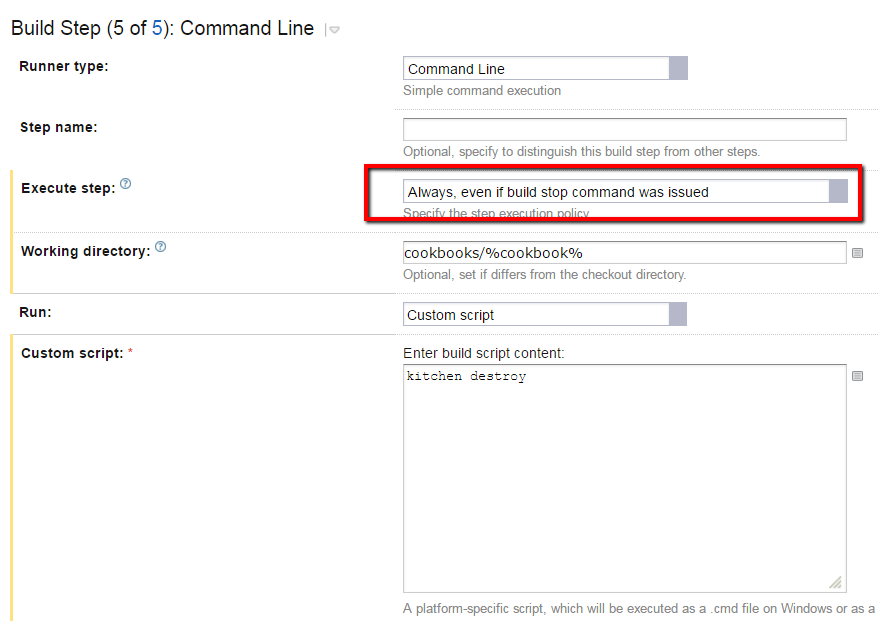

5. Kitchen Destroy

If the above test fails, it’s important to not keep the virtual machine running. This is especially true if I’m using the azure runner. So at the end I’ll call kitchen destroy, and always call it, even if the previous command failed:

Build Agent Setup

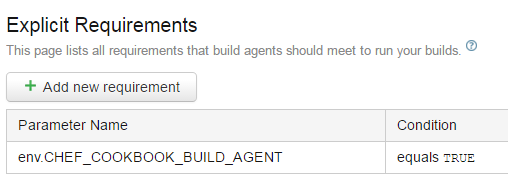

As I mentioned earlier, our build agents are set up through Chef itself, so configuration of them is easy. Since we are creating our Chef Projects inside the product’s projects, we don’t want to mix their build agents with the Chef ones. We keep them separated because we let each team have their own build agents that they manage. To solve for the mix, we add the Chef subproject set up above to our own Chef build agent pool. Then in our template, we add a build agent requirement:

In our recipe for the build agent, we set this environment variable, so this limits our cookbook builds to only run on build agents on which our Chef recipe has run.

Triggering

Finally, we want to trigger this cookbook build whenever something in the cookbook is checked in. We do this through adding a VCS trigger with the default settings to the template.

Conclusion

With the template in place, it takes about ten minutes to add a team’s cookbook to be fully tested and built within their own environment. It feels very much like a software build, which is fantastic for everyone because it reminds us that the infrastructure code we are creating is like any other code; it should be subject to automation just like the rest.